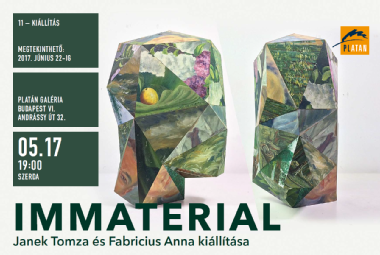

IMMATERIAL - Fabricius Anna és Janek Tomza közös kiállítása | Fabricius Anna, Janek Tomza

kurátor | Tomasz Piars

megnyitó | 2017. május 17. 19:00

web | http://polinst.hu/node/11196

a kiállítás bezárása | 2017. junius 22.

cím | Platán Galéria, Andrássy út 32.

IMMATERIAL

Fabricius Anna és Janek Tomza közös kiállítása a Platán Galériában

Megnyító május 17-én 19.00 órakor

---------------------------------------------------------------------

IMMATERIAL explores common threads in the time-based works of Anna Fabricius and the studio-based sculpture of Jan Tomza. In English, immaterial pertains to metaphysics, but also something discarded, irrelevant, out of context. While working in different media and paradigms, the artists use both these meanings as one to employ questions on removal, de-contextualization and de-materialization.

In a post-industrial society, immateriality is habitual – personal technology makes it easy to extract ourselves from material reality, and even easier to overlook the complex infrastructure which exists to support this extraction – especially since so much of it is in China. In a 2016 book, “An Archaeology of the Immaterial,” Victor Buchli argues that "the immaterial is by no means a unique quality of late capitalism or modernity but a thoroughly ‘un-modern’ aspect of human activity that has a long, if poorly understood, history.” A common feature of both post-industrial capitalism, Christian asceticism and reformation, as well as leninism – Buchli analyses the denial of materiality within contrasting social systems that nonetheless unite in making sure that matter always draws the shortest straw, and traces this denial to a particular view of the body – as a disposable vessel for the soul.

In comparison to a denial of such scope, forgetting the reality of manual labour in the industrial era seems like a triviality too ambiguous to include, as would be treating virtual entertainment to anything more than the occasional health warning. In their works for IMMATERIAL, both Fabricius and Tomza employ elaborate means to reconstruct these trivialities – a pantomime of factory work becomes an insightful choreography, and models from computer games become statues. In both cases, the triviality is a broken connection within material culture – what is left is either only the social, or only the material.

Anna Fabricius can be said to engage in a sociology of disappearing within a socjety which no longer, perhaps not yet, manufactures. We see a factory floor emptied of machinery, and workers performing particularly intricate routines on inexistent machines. The artist’s classically composed shots, polished form, and insistence on uniform all signal a coherence, but deny the full picture – engaged in the same state of play as the one documented, viewers follow the movements and memoir-like voiceover, recalibrating their intellectual devices from contemporary or absurdist theatre to retune to a supposedly trivial activity.

Fabricius approaches her subjects with extraordinary empathy – instead of assigning identities or roles within vertical discourse, she invites them to participate in a child’s game about adult work in which they play themselves. Their personal experience, precision, and expertise lets them learn through telling viewers about the tools and techniques they came to master to free society from tools and techniques. Such a creative strategy pays off handsomely – children's games allow for an unabridged, deeply subjective and insightful view on manual labour and a disappearing workplace.

Janek Tomza’s sculptures examine another disappearance – that of traditional, representational painting. Far from the contemporary art market, a no longer relevant tradition of art is now valued below the cost of the materials required to produce it. Horses, flowers, estates, determined men and naked women – the salt of how the West once construed the world – now litter flea markets like plastic beads in the sand. Since the financial turn to speculation in the 1980s, the West has seen manual labour's drastic decline in value coincide with a decline in its value within the sphere of art. Along came virtualisation – the new site where culture is created and crosspollinates freely. It is thus none other than technological progress, the unimaginably complex engagement and ordering of matter, to have sent the immaterialist fantasy of freedom through disembodiment (“Die gedanken sind frei”) to new heights. Today, some take its paradigms as the status quo, going on to propose we reapply their logic throughout, as proposed explicitly by a initiator and speaker at a conference on a new area of research - archaeogaming - which took place in Holland in 2016. One of his blog posts suggest that "There is No Difference Between “Real” and “Virtual” Culture."

Echoing a highlight of Buchli’s analysis, that “the immaterial is only realized in the most emphatic material terms,” Tomza cut and assembled flea market paintings into the most emphatic objects found in best-selling computer games – heads, limbs, and intestines. In the end, they resemble neither the representation, nor the represented form, and in this way GIBS underscore the material cost of immaterial pursuits.

IMMATERIAL engages the complexities of labour by excluding its rationale from the equation. A cable assembler works on a utilitarian product, which we never observe but use every day, and a painter works on a useless object, which we judge but don't directly use. If we can tell by monetary value, the rationale of manual labour - whether creative or repetitive - isn't faring very well. The artists' engagement highlights how across systems, the narrative on manual labour and embodiment is strong only by the sheer persistence of its marginalization, while the effortlessness, high pace and responsiveness of virtual reality is takes over from freedom, fluidity, and agency.

Térkép

Ne elégedjen meg az artKomm levelek olvasásával! Az ikOn weboldalán sokkal több információt talál az eseményekről.